Iskander Mirza's Exploitation of IMINT for Politico-Diplomatic Stability

Pakistan's first President was historically familiar with the power of IMINT

Major General (Retired) Iskander Mirza, who went on to become Pakistan's first President, spent the later part of his life in exile in the UK. He was subjected to a vicious mix of betrayal, treachery and conspiracy led by then army chief and military dictator, General Ayub Khan.

Mirza was a witness to some of the most remarkable periods in the Indian Subcontinent's history. After service in the erstwhile Royal Indian Army, he moved into the British civil service which in the early 20th century allocated quotas for military officers to be inducted in the Indian Political Service. He served on multiple stints as regional administrator in Undivided India including erstwhile North West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkha province of Pakistan) and erstwhile Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). It was but natural and expected of Mirza to have maintained official logbooks and personal journals throughout his long career.

While these were destroyed to a great extent by General (later self-proclaimed Field Marshal) Ayub Khan, a few memoirs survived and by good fortune used by biographers such as the prodigious Ahmad Saleem (late) in 1997 and, most recently, by Syed Khawar Mehdi in 2023. Both these books offer valuable insights into Mirza's impeccable mind. For the astute observer, several anecdotes related to exploitation of intelligence can also be found.

One such less-known incident is the exploitation of Imagery Intelligence (IMINT) or aerial reconnaissance imagery of the time for official use, which both authors have covered in their books.

In April 1938, Iskander Mirza (Indian Political Service) was appointed Political Agent of Khyber Agency. An incident of security and diplomatic significance occurred in October 1939, one month after the outbreak of World War II, in which two dissident sardars (nobles) of the Afghan Royal Family (then headed by King Muhammad Zahir Shah) fled to Tirah and were given refuge by Nawab Zaman Khan Kuki Khel.

The two sardars, whose identities are not disclosed, were conspiring with a lashkar (militia) of the Malikdin Khel Afridi tribe led by Khushhal Khan, who was a known "rabble-rouser" for British colonial authorities and had participated in the large-scale anti-British mobilisation of 1930s alongside other mullahs allied with agitational political parties in the Frontier against a common enemy.

This time around (1939), Khushhal Khan's lashkar had joined with the two dissidents to march into Kabul and 'vanquish' the Afghan royal family, which was a strategic issue of concern for the British Empire despite Shah's government proclaiming to be completely sovereign.

As Amanda Lanzillo provides context to the regional geopolitics:-

"The Anglo-Afghan Treaty of Kabul in 1921—an outcome of the conference and the subsequent negotiations—is usually characterized as establishing Afghanistan as “officially free and independent in its internal and external affairs.” But in reality, in the post-1921 period Afghanistan was continually subject to forms of economic and political subordination to the British Empire. Over forty years of formal quasi-coloniality, from 1880 to 1919, had left Afghanistan’s economy deeply intertwined with and dependent on the British Empire, and especially British India."

...

"Muhammad Nadir Shah, Amanullah Khan’s former minister of war, reestablished dynastic rule in late 1929. Born and raised in Dehradun, India, Nadir Shah, like rulers before him, did attempt to lessen Afghanistan’s dependence on Britain. Like his predecessors, his court attracted advisors from across Europe and the Middle East, especially from Turkey and Germany. But his court remained partially funded by British loans, and the infrastructure of the country heavily dependent on British “gifts.”

Indeed, the search for other international partners ultimately gave way, under Nadir Shah’s son, Zahir Shah (r. 1933-1973), to Afghanistan’s position, in the context of the Cold War, as a centre for competing Soviet and American ideologies and practices of “development.”"

It was but a matter of immense importance that the Afghan royal family as a symbol of apparent stability be sustained lest the country returned to lawlessness and chaos. The British Empire could ill-afford the formation of a chaotic buffer to its west which could be exploited by its temporary wartime Soviet ally.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) had previously carried out multiple air attacks against tribal lashkars since the initial mobilisation in 1930, which were based on aerial reconnaissance. Since the lashkars were familiar with the lethality of such attacks and retreated, Nawab Zaman Khan Kuki Khel was personally informed (read: warned) by Iskander Mirza that he had aerial photographs of his two homes in Tirah valley which were marked for RAF's bombing, if necessary; these were likely part of the Nawab's fort which remains standing to this day (see on Google Earth or Maps).

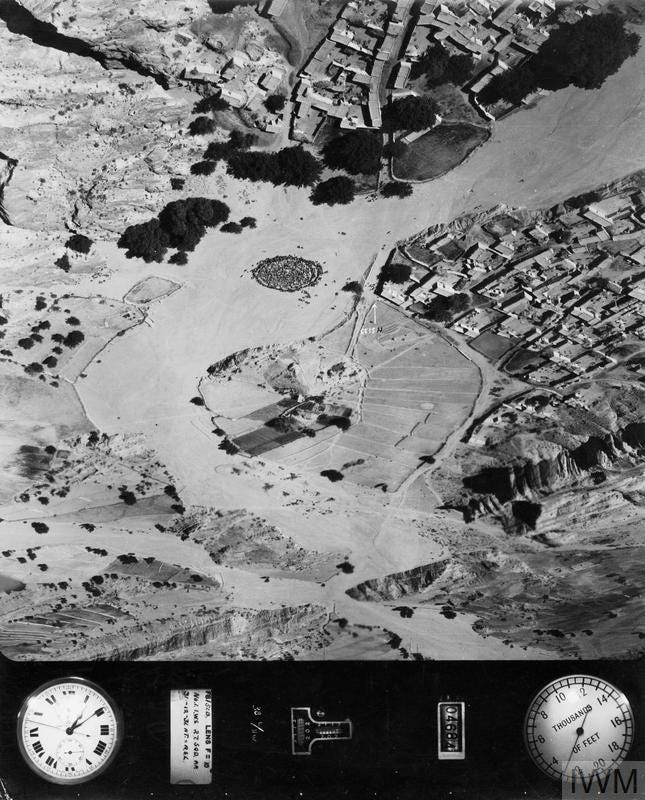

The RAF had three operational bases near the Frontier: Kohat, Peshawar and Risalpur. The No. 27 and No. 60 Squadrons comprised a fleet of Westland Wapitis fitted with Fairchild Type F8 aerial cameras.

An actual image from the colonial-era Frontier captured by an RAF Wapiti of the No. 27 Squadron is reproduced below:

© IWM HU 91197 Non-Commercial Use

The prospect of having his complex bombed encouraged the Nawab to hand over the dissident sardars who were returned to Afghan authorities, thus sending a positive gesture to the Shah on behalf of the British Crown.

Nawab Zaman Khan may have also relented because he was among the pro-British tribal elders whose 'active loyalty' had been documented by colonial authorities and he was posthumously awarded the title of 'Khan Bahadur' (Brave Leader) by the Crown. His connivance with the Afridis would have been understandable given that he commanded the tribe for almost a century and was consequently beholden to them.

This fascinating account reveals how the Political Agents in British-era Frontier areas not only had access to Special Branch reports but also IMINT. It is less likely that Mirza alone was given visibility of such reports for bargaining with inhabitants of his jurisdiction.

References

'Iskander Mirza - Rise and Fall of a President' by Ahmad Saleem

'Honour-bound to Pakistan in Duty, Destiny & Death - Iskander Mirza' by Syed Khawar Mehdi

'RAF Kohat - 1941 (Frank Powley's Collection)', RAF Commands, https://www.rafcommands.com/galleries/SEAC/RAF-Kohat-1941

'Royal Air Force Aerial Reconnaissance on the North-West Frontier of India, 1919-1939', Imperial War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205022513

'PAF Peshawar', Global Security, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/pakistan/peshawar-ab.htm

Amie Gordon, 'Exploring the North West Frontier from 21,000ft: RAF pilot's fascinating 1930s reconnaissance snaps of the Himalayas and Indus Valley emerge for sale more than 80 years on', Daily Mail Online, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6209685/RAF-pilots-1930s-reconnaissance-snaps-emerge-sale.html

Hugh A. Halliday, 'Above Enemy Lines: Air Force, Part 27, Legion Magazine, https://legionmagazine.com/above-enemy-lines-air-force-part-27/

Polly Singh, 'A flight of Eagles : The Westland Wapiti in Indian Air Force Service', Vayu Aerospace Review, Issue VI/2003

'Frontier of Faith: Islam in the Indo-Afghan Borderland' by Sana Haroon

Amanda Lanzillo, 'Empire and Dependence in Afghan History', Jamhoor, https://www.jamhoor.org/read/empire-and-dependence-in-afghan-history

'Summary of the Principal Events and Measures of the Viceroyalty of His Excellency The Earl of Minto from November 1905 to July 1910 - Vol I: Afghanistan, North-West Frontier, Chinese Turkistan-The Gilgit Agency', Foreign Department, https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.206583/2015.206583.Summary-Of_text.pdf

'Afridi (Pashtun)', Academic, https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/451232