The intent behind writing this article is to document the profile of an Indian-origin police officer who performed intelligence duties on behalf of the British Crown and Government of (Undivided) India, leading up to the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent.

The Partition in itself was a massive source of generational trauma induced by communal killings and mass migrations between new borders of independent India and Pakistan. It has been well documented by eminent historians that millions of lives were up-ended during this phenomenon. Little is known, however, about the impact it had on the Crown's civil subjects in the new states, perhaps because there remains a general assumption that bureaucrats (and for that matter military personnel who migrated) must have had a ‘smooth sailing’ for them. This assertion is, however, unsubstantiated.

This story is about one such police officer, Ghazanfar Ali Naqvi, more generally referred to as G.A. Naqvi or Major Naqvi.

Profile

G.A. Naqvi was born on 17 April 1902 and was commissioned as an officer in the Indian Police (IP) during British colonial rule in the Indian Subcontinent. He hailed from United Provinces (UP).

Known Academic History: MA and LLB from Aligarh Muslim University, Undivided India (1925)

Known Professional History:-

Commissioned as Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP) (27 May 1926)

ASP and later Officiating as Superintendent of Police (SP) across UP including Etah and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) (1933-1941)

Assistant Security Officer/ commissioned rank of Major in the British Indian Army in the British Legation at Tehran, Iran on deputation from the Government of India's Home Department (1942-43)

Training at Intelligence Bureau (IB), Undivided India (1943)

Consular Attaché in the British Legation in Tehran, Iran on deputation from the Government of India's Home Department (1943-45)

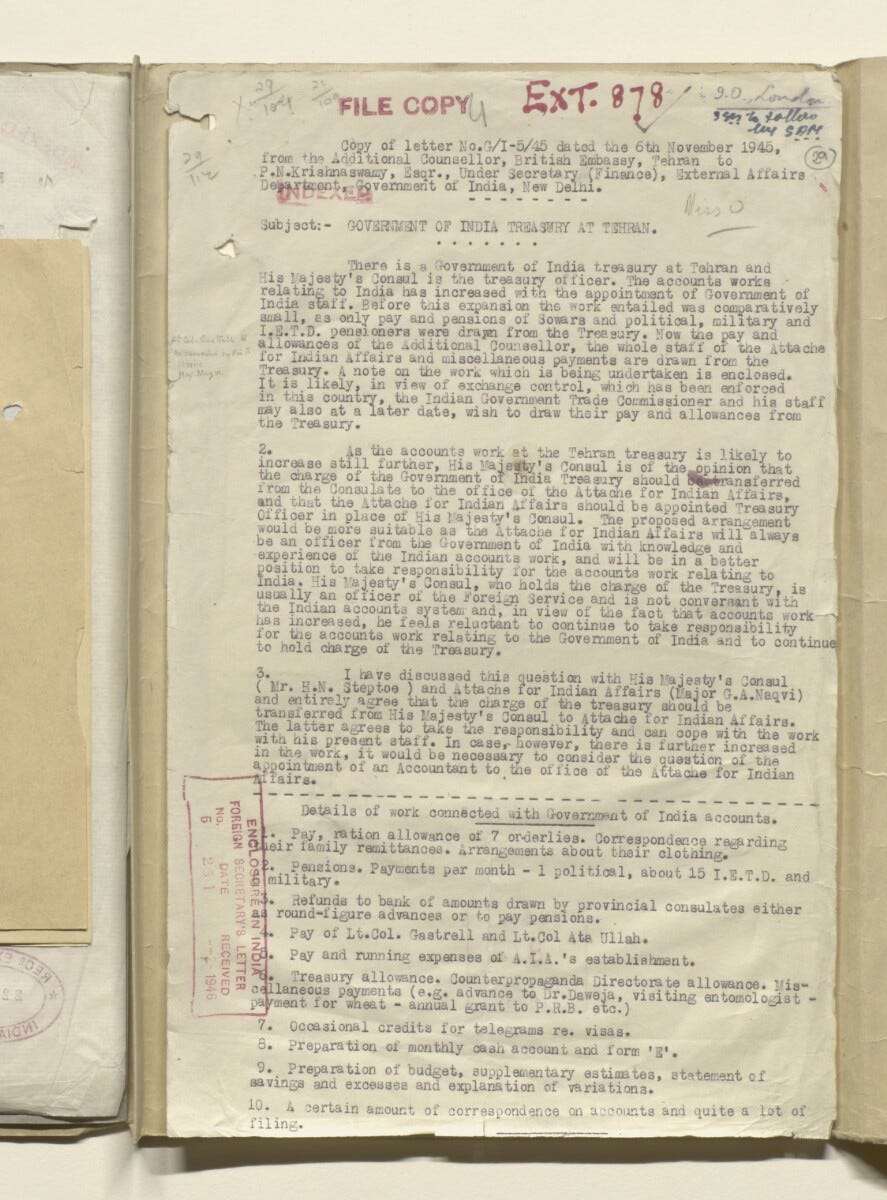

Transfer from Home Department to newly-raised External Affairs Department, Government of India and designated as Additional Consul for Indian Affairs; the British Crown officially referred to this designation as 'Attache for Indian Affairs' (1945-47)

Stints in Iran

Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany had announced war on then Soviet Union in June 1941. Sensing danger to British energy and security interests in the Middle East/ Near Asia, the British Crown decided to form an alliance and prevent a feared German Army takeover of Iran. This led to the famous Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in August 1941 that culminated later with a Tripartite Treaty of Alliance (against Nazi Germany) between Iran, Great Britain (GB) and the Soviet sting.

Declassified MI5 records reveal that Naqvi (referred to also as 'Nagri') was infact seconded to the Defence and Security Office Persia (DSO Persia) as Investigation Officer (Indian Suspects) and his posting within the British Legation was just for official cover. His priority task was to keep an eye on suspicious activities of Indian citizens in Iran who were anti-British and pro-Axis. Though he possessed experience of investigations during service in the CID (India), he was not formally trained in spycraft and transferred briefly to IB for requisite training.

Major William Magan (later Brigadier), the legendary MI5 officer popularly referred to as 'Bill Magan', was posted in DSO Persia as Liaison Officer on behalf of Undivided India's IB and played a critical role in developing a network of 'stay behind agents' who would provide intelligence in case the Nazi German Army was successful in occupying Iran (which, as history shows, never came to pass). Magan did not recruit operatives directly but reportedly delegated recruitment duties to three "assistants", including an unnamed Indian police officer serving as 'Vice Consul' in Yazd; this is most likely a reference to Naqvi who was deputed on behalf of the Home Department (1942-43) but this still does not explain why he would 'assist' another officer of equal rank [remember that Naqvi was commissioned on Major rank prior to departure from India].

A breakthrough was achieved in 1943 when, based on Naqvi's report, a group of Indians was arrested for illegally attempting to cross the Indo-Iranian border; all the suspects were merchants of Sikh faith who were permanently expelled from Iran and their activities dubbed as 'prejudicial' to both India and Iran. Subsequently, Naqvi was accused of communal bias by the Sikh community in both countries and, rather astonshingly, some of his secret reports held by the British Legation were apparently getting leaked. Cognisant of this matter, Naqvi had issued another correspondence prescribing measures to prevent diplomatic leaks. His term in Tehran during and after this incident, well upto his early retirement, indicates that Naqvi had struck a very negative chord with the Sikh community who frequently agitated and complained against him. All this, despite being cleared of accusations through department inquiries.

In August 1946, the UP government wrote to Delhi (Government of India) requesting Naqvi's return because communal tensions across the province necessitated the retention of an on-site Muslim police officer. This request was turned down by then Interim External Affairs Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (later first Prime Minister of independent India) who wanted to retain Naqvi's services in Iran for an additional year.

Partition and its Problems

During the run-up to Partition, it was time for civil and military subjects of the British Crown/ Government of (Undivided) India to decide if they wished to continue service in India or migrate to Pakistan. Naqvi had initially expressed his willingness to stay in India as he was unaware of his family's status (choice of country) and he was, per his claim, not properly aware with politico-socio developments taking place back home.

Unfortunately, Naqvi's parent UP government which was very eager to have him repatriated a year ago changed its attitude and transformed into a sort of communal observer. His choice to remain in India, despite being a Muslim, was viewed suspiciously by then UP government which bluntly stated officially that they did not require his official services anymore. In fact, Naqvi's case file was regularly swapped between the External Affairs, Home and UP government departments so many times that Naqvi eventually decided to put things to rest. Meanwhile, he had realised about the actual predicament and had intimated his request to change his option from 'India' to 'Pakistan'.

Records show that Naqvi took very few leaves to visit India and was spared on few occasions. In a recommendation letter to Secretary External Affairs Department dated 21 October 1947, then British Charge d'Affaires in Tehran M.J. Creswell acknowledged that Naqvi could not be spared on account of "pressure of work" and was only spared in September 1947. His term with the British Legation officially ended on 7 November 1947. Since 15 August 1947, he was on the payroll of the British government and was employed by neither governments of newly-formed India and Pakistan.

Time and circumstances were opposed to Naqvi's change of option too. The later Muslims emigrated from India after Partition, the more they were viewed with suspicion. Naqvi's case was sent to Pakistan by the Partition Secretariat via External Affairs Department. To the latter's surprise, in November 1947, they received a response from Agha Hilaly that the Government of Pakistan was "unable to accept Mr. G.A. Naqvi's change of option"; Hilaly was an Indian Civil Service officer from Madras cadre (commissioned 1936) who was corresponding on behalf of the Secretary to Government of Pakistan [he would later be appointed on multiple diplomatic postings overseas, including India and become Foreign Secretary during premiership of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto].

Contrast Naqvi's perplexing predicament with that of his IP contemporaries from UP (India): Ghulam Ahmed was absorbed into a new Police Service of Pakistan (PSP) and appointed first Director of Pakistan's IB on 1 August 1947 [reportedly with the founding father Muhammad Ali Jinnah's consent]. His friend Syed Kazim Raza was also included in the PSP cadre and succeeded Ghulam Ahmed as second Director IB. Muhammad Abu Zafar (M.A. Zafar) was absorbed also into PSP and served as Deputy Director IB including during Kazim's headship of IB [Kazim Raza and M.A. Zafar both have been earlier documented engaging Haji Jelaluddin Wang Zengshan for Chinese translation work]. Perhaps these experienced police officers from UP were fortunate to have migrated well in time before ethno-nationalism seemed to have seeped in Sindh and West Punjab (Pakistani Punjab). By early 1948, Sindh and West Punjab governments had started to prioritise intake and retention of officers who belonged to their territories and had become discriminatory toward officers from UP.

Faced with dim prospects, Naqvi once again relented and had to forgo several financial benefits including full pension and denial of compensation from the Government of India. For little over two years, he was unable to manage expenses after moving to Karachi, Pakistan during his period of Leave Preparatory to Retirement (LPR). In early 1948, he requested the Government of India to allow him to start a business or get private employment but this request was also shot down citing relevant LPR rules. Barring one or two instances, Naqvi was last known to have accompanied Syed Kazim Raza to visit then Defence Secretary Iskandar Ali Mirza in 1953, just prior to his imposition of a temporary martial law in Lahore.

There are no further records or mentions of Naqvi in the Pakistani government and media archives whenceforth. There exists a likelihood that he may have been accommodated by his former IP contemporaries for work somewhere, but this remains a strong speculation.

Conclusion

Ghazanfar Ali Naqvi's is a uniquely perplexing case of a career officer who diligently performed his duties in Iran but could not make himself physically available at a critical turning point in his homeland's history. He left for service to Iran as an employee of the Government of India but returned as a rather 'stateless' subject, viewed with suspicion by his parent government (India) and further disowned by his new choice (Pakistan).

It is even more surprising that despite service experience in CID and IB, he was ‘discarded’ so brutally and left to fend for himself. We can only imagine what his destiny would have been were he allowed to repatriate to UP in 1946 by Nehru.

References

India Office List (1930)

India Office List (1935)

The Combined India and Burma Office List (October-December 1937)

India Office and Burma Office List (1940)

A.H. Hamzavi, "Iran and the Tehran Conference", 11 January 1944, https://watermark.silverchair.com/ia-20-2-192.pdf

Imran Matanat, Aligarh Muslim University Alumni Directory, January 2012

Adrian Dennis Warren O'Sullivan, "German Covert Initiatives and British Intelligence in Persia (Iran) 1939-1945", doctoral thesis for University of South Africa, June 2012

Dr Rakesh Ankit, "G.A. Naqvi: from Indian Police (UP), 1926 to Pakistani Citizen (Sindh), 1947", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 28, Issue 2, April 2018, pp 295-314