Haji Jelaluddin Wang Zengshan’s Engagements with Pakistani Intelligence Agencies

The Chinese Muslim intellectual was a member of the Kuomintang and briefly undertook translation work for Pakistan's civilian and military intelligence agencies

From 1951 till 1954, Pakistan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Commonwealth Relations (MoFA & CR) benefited from the translation services of a Muslim citizen of China. Apart from translating and interpreting documents in his native language, this employee was also occasionally solicited to provide similar services to cater for Turkish language matters.

Unbeknownst to many, at the time, was that this translation officer was not an ordinary Chinese Muslim working for the MoFA & CR but an astute intellectual of Islamic history; he was also a mid-ranking political member of the "Guomindang" or "Kuomintang (KMT)", rivals of today's Communist Party of China (CPC) who formed their own republic known as Taiwan.

But how did Wang end up working as a translation officer for Pakistan's diplomatic establishment, out of all places? For a better understanding, it is necessary to take a brief dive into the annals of history. Resourceful information was made available courtesy of digitised archives hosted by the National University of Singapore (NUS) and known as The Wang Zengshan Private Papers (WZSPP) Collection. They consist of correspondence, diaries, speeches, telegrams, photographs and reports which covered Wang's personal and professional lives during the 1940s and 1950s, especially the period after he left China. Historians are grateful to the late Dr Rosey Wang Ma, one of Wang's daughters, who deposited the Collection to NUS.

Brief Profile

Wang was born in 1903 to a Hui (Muslim) family in Linqing, Shandong province of China, a recognised East Asian ethnoreligious group distinct from the Uyghurs in that a vast majority of them speak native Chinese as compared to Turkic languages. His father moved him to Beijing for schooling and further educational purposes.

He rose through the ranks to a mid-level position as part of the so-called 'Hui Muslim elite', but not in the conventional understanding of the term. For proper insight, I highly recommend you read this insightful paper by Taiwanese scholar Zheng Yueli. Wang would travel to multiple Muslim countries representing Chinese Muslims. Upon his return, while the Second Sino-Japanese War was still ongoing, Wang lived in Nanjing and Chongqing.

Near the end of September 1949 and just before the CPC's Mao Zedong declared China as a People's Republic, Wang successfully emigrated to Pakistan along with his big family, a few contemporaries and reportedly also some KMT military figures; their primary objective was to avoid persecution under the new regime. They crossed over into Jammu & Kashmir and entered Lahore, before eventually heading south to then-capital Karachi. During his sojourn in the metropolis, Wang provided translation and interpretation services to nascent Pakistan's diplomatic and security establishments.

In 1955, despite being nearly-eligible for permanent residence in the country, he decided to move with his family once again, returning to Türkiye and finally settling there until his death in 1961. Some of Wang's children and their further offspring are today scattered across the globe but Türkiye remains their adopted home since decades.

Known Academic History:-

Schooling in Beijing

Graduation from Yenching University in Beijing, China (1925); the institute went defunct in 1952

Masters in History from Istanbul University, Türkiye (1930)

Known Professional History:-

Induction to the KMT Legislative Council (1931)

Active member of the Chinese Muslim Youth Association and also its newsletter's editor; wrote several articles about the Islamic world and opportunities for Chinese Muslims to study in Türkiye

Following the eruption of Second Sino-Japanese War (1937), KMT's prominent Muslim leader Ma Tianying successfully convinced the party to send a delegation to the Middle East/ Near East countries for diplomacy; their purpose was to secure support against Imperial Japan. Wang led the group of five Chinese Muslim delegates (Ma included) to 13 Muslim countries where they interacted with host political elites, addressed citizens in mosques and participated in meetings of different Islamic organisations (1937-39)

KMT Commissioner of Civil Affairs in the Xinjiang Coalition Government (1946-47)

Employment with MoFA & CR, Karachi, Pakistan (1951-55)

Employment with Istanbul University, Türkiye (1955-61); Wang was requested to setup the country's first Department of Chinese Studies

Honourary Representative of the Republic of China (Taiwan) in Istanbul, Türkiye (1955-61)

Wang's Sojourn in Pakistan

Although he had crossed over into Pakistan right before the CPC's takeover of Mainland China, Wang was not immediately offered any government position. Primary and secondary records to this effect are not available. Wang's archived diary notes only confirm that he formally took up employment with Pakistan's MoFA & CR in September 1951, working initially out of their office in Bhopal Palace before they were re-accommodated to the Mohatta Palace. These were the initial days of an independent Pakistan and the country's important ministries (including defence and intelligence establishments) were headquartered there [it was more than a decade after Wang's departure from Pakistan that Islamabad was declared as the new federal capital].

A thorough examination of the WZSPP Collection informs us that Wang was serving in a relatively 'unglamorous', though important, position in Pakistan's diplomatic machinery. He was employed in its 'Research Branch' and was frequently tasked with translating and interpreting Chinese documents. We also come to know that he was frequently instructed to accompany diplomatic luminaries such as Professor Ahmed Ali (Pakistani intellectual and then-former Charge d'Affaires in China) and Fida Hussain (later Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's envoy in New Delhi) to Palace Cinema. Their job was to inspect movies made under CPC rule and determine any grounds for censorship [CPC diplomatic personnel would also be present on the occasion].

Throughout his stay, Wang was also in regular correspondence with fellow Hui Muslim named Omar Pai Chung-hsi, more popularly known as Bai Chongxi. Bao was the KMT regime's first Minister of National Defence (1946-48) who, upon moving to Taiwan, was appointed Vice Director of the Strategic Advisory Commission in the Presidential Office. They usually discussed issues affecting the Islamic world in general and Chinese Muslim affairs in particular. There is no indication that Wang ever communicated privileged information which he had access to on account of his employment with the MoFA & CR.

Of particular importance, however, is Wang's occasional engagements with Pakistani intelligence officials. Archived records reveal that between the end of 1952 and early 1953, he interacted on six different occasions with senior officials of the Intelligence Bureau (IB) including once with an officer of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

A brief summary based on my personal assessment is presented below followed with digital copies as supporting evidence:-

Interaction with IB

(1) Wang went to see Director IB Kazim Raza on 29 February 1952. In the record, Wang marks the letter to "A.S.P." (Assistant Superintendent of Police) which was marked to A.M.S. Ahmad with designation mentioned as "A.D. (F)"; it is speculated to be Assistant Director (Foreign) or similar. Ahmad, himself a police officer like his boss, was perhaps deputed as a liaison with MoFA & CR by the IB [Historical Nugget: Raza was commissioned in the imperial Indian Police from Uttar Pradesh and was mentioned in King George V's 1930 Honours List. Ahmad hailed from erstwhile East Pakistan and was a son-in-law of Pakistan's second Interior Minister, Khawaja Shahabuddin].

A distinct entry was inserted, perhaps on a later date, below Wang's signature block. It contains a box with Mandarin scribbled on it with the names of Director IB and AD IB underneath. The Chinese text roughly reads:

"The job is to review the passports of Chinese Communist Party personnel (those who come to Pakistan for participation in industrial exhibitions)"Based on this entry, we can proffer with a good degree of confidence that, among other things, Wang's input was sought by the IB to detect the infiltration of any ideologically-disruptive elements posing as industrialists or trade representatives.

Analysis of the handwriting containing details of the work and names of the two officials confirms it belongs to Wang; similar writing style was observed for Mandarin and English text in his private diary and other papers.

(2) Wang met Deputy Director M.A. Zafar on 23rd December 1952, 30th December 1952 and also on 2nd January 1953. Zafar, who was a serving police officer seconded to the IB, reportedly told Wang that he had obtained permission from the Chief of Protocol (CP) at MoFA & CR to solicit Wang's services on-call, as and when required.

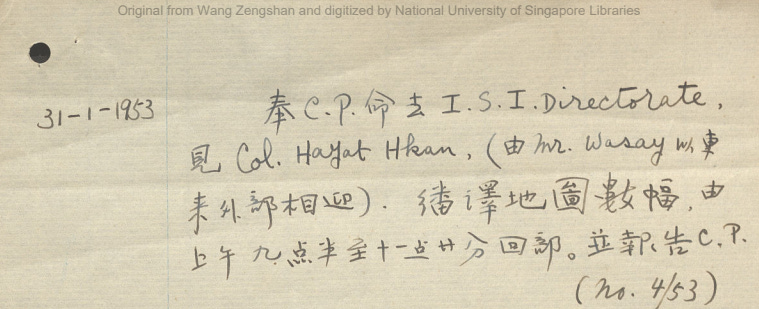

Interaction with ISI

On 31 January 1953, Wang went to the ISI Directorate in Karachi to see one "Colonel Hayat Khan" where he was welcome by one "Mr Wasay" (civilian officer?).

Details about tasking are not known from the official memo, but a raw entry in Wang's private diary mentions that the work involved something to do with maps/ cartography.

This is intriguing in itself, however absence of further details prevents us from any informed speculation as to the nature and scope of the type of maps he was asked to interpret.

It is important to note that following the botched 'Rawalpindi Conspiracy' of 1951, then Army Commander-in-Chief General Ayub Khan had initiated a purge across the army which included a change in ISI's leadership. Brigadier Mirza Hamid Hussain was replaced in May 1951 (two months after the coup attempt) by Colonel Muhammad Afzal Malik, whose tenure ended in April 1953 [the only Colonel rank officer to have tenured the agency throughout its history]. In this backdrop, the presence of a Colonel-rank officer (Hayat Khan) seems unlikely; he may have been a Lieutenant Colonel serving as General Staff Officer-I (GSO-I), as per norms.

Information on Hayat is scare and it could be a reference to Brigadier Muhammad Hayat, later the agency's seventh chief (1957-59), though this remains a mere speculation.

Contextual Analysis

We have to consider the fact that although the CPC had taken leadership of China in 1949, it was only in mid 1951 that diplomatic relations between the two were formally established; Pakistan had also dissolved relations with and recognition of the Republic of China regime which ruled Taiwan. The period 1951-53 was also one marked by high-level Pakistani leaders visiting the US including Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan, Army Commander-in-Chief General Ayub Khan, Foreign Minister Zafrullah Khan, Foreign Secretary Ikramullah, Finance Minister Ghulam Muhammad, Defence Secretary Major General Sikander Mirza and special envoy Mir Laiq Ali.

These back-to-back visits were the earliest indications, in retrospect, of Pakistan's and in particular its security establishment's tilt to the US [Ayub would later solidify these after imposing martial law and forming an alliance]. In parallel, the IB under its first chief (Ghulam Ahmed) was eager to establish a high-level intelligence relationship which would include deputation of a liaison officer, an offer which received zero enthusiasm in Langley, at least during the early-to-mid 1950s. The CIA was, however, benefiting immensely from IB's deep research on Communist tentacles across Pakistan as it held a rich repository of institutional knowledge passed down from its colonial origins.

In short, the 1950s and 1960s were a period of extensive security and defence cooperation with the US which, by-and-large, enjoyed the support of different political regimes in the federal capital (Karachi and later Islamabad).

I believe that if Wang had engaged on any other occasion with intelligence officials in Pakistan, they would have been documented as meticulously as he did. That he maintained a record of his correspondences is impressive, though one cannot discount the brief (though very much plausible) possibility that not all documents may have been preserved carefully.

Some observers would proffer Wang may also have chosen to keep certain meetings off-the-record, which I personally find unconvincing. If he documented interactions with ISI and IB officials, no less than chief of the latter, I do not see a reason why he would not disclose others. It can be said confidently that Wang was vigilant and mindful of sticking to the proverbial "proper channel" before engaging with officials outside his designated purview. He was, after all, a KMT refugee and would have liked not to appear suspicious.

Wang as an Intelligence Operator?

Available information, based on WZSPP Collection and scholarly work on Wang's history, do not mention involvement in any military of espionage work while serving the KMT regime in pre-1949 China, let alone Pakistan.

I will go so far as to add that a deeper study of Wang's notes reveal he faced financial hardship in Pakistan, even during his official employment; he had a large family and he was once denied reimbursement of hospital charges accrued on account of his wife's admission on grounds of typical Subcontinental bureaucratic observations that the hospital his wife was in was not in the government's panel of approved ones. In another memo, he also lamented being deprived of annual increment in salary after one year of service.

Unlike Bao Chongxi who, despite having a fall-out with Chiang Kai-shek in later life, remained a respected figure in KMT circles and was duly honoured on death; Wang was in a relatively middle-tier cadre of officials who were not directly (read: in-person) involved in KMT activities post 1949. Furthermore, there is no credible evidence to infer even remotely that Wang was installed 'under cover' in the MoFA & CR. His simple lifestyle, contents of correspondence with Bao and engagements with Pakistani religious thought-leaders viz World Muslim Conferences etc do not suggest a pattern of someone who is working as an operator.

Therefore, as far as available records are concerned, Wang interacted with Pakistan's intelligence establishment for less than a year (February 1952-January 1953).

Later Life

After his departure from Pakistan to Türkiye, Wang's salary as a university lecturer was unable to sustain a family of 9 dependents (wife and 8 children). He opened the first Chinese restaurant in suburban Istanbul, which was primarily managed by his wife Fatma. It was closed down within a few weeks because of a fallout with Wang's business partners.

The couple later setup shop in the city's famous Taksim Square (European side) named 'Cin Loktantasi' ('Chinese Restaurant'), which reportedly thrived and was decent enough to not just sustain their family but also give all children quality education. They were able to setup branches in capital Ankara, Gocek and Marmaris.

These restaurants were shut down in 2002 by one of Wang's sons, Isa. In 2006, however, he once again setup a restaurant in Istanbul: one managed by himself named 'Mai Ling' on Baghdad Avenue (Asian side of Istanbul) while one of his younger brothers, Kurban, operates the 'Chinese Wang Restaurant' on the European side of the city at Istinye Shooting Range.

Conclusion

At a personal level, the WZSPP Collection has proven to be a goldmine of resourceful information for researchers on Chinese Muslims. It is deeply unfortunate that Haji Jelaluddin Wang Zengshan remains unknown to Pakistani historians, not least his status as a KMT refugee.

I endeavoured to write this detailed essay on Wang in the hopes that it brings to fore his services for Pakistan's diplomatic and security establishments and also motivates local historians to research further into the attempts of Chinese Hui Muslims in early 20th century to promote an ‘Islamic Renaissance’. The predominant assumption in Pakistan seems to focus solely on the ethnic Uyghurs and not the Hui.

The WZSPP Collection also contains highly resourceful information for Islamic/ Muslim historians on Bai and Wang's efforts to secure stakes for Chinese Muslims in contemporary Islamic discourse, since the largely-atheist CPC led overwhelmingly by ethnic Han had more important things to focus on than welfare of Chinese Muslims. Beyond religion studies, these digitised archives offer value for sociologists and particularly ethnologists.

Lastly, Wang's notes on his engagements with Pakistani intelligence officials helps us understand how seriously counterintelligence viz China was during the formative years of an independent Pakistan, something which seems unbelievable considering today's extraordinary relations with the CPC.

You may also be interested in reading: Japan’s Counter Intelligence Operation in Newly-Independent Pakistan (04 January 1954)